Books: I love them! And many people like me prefer to hold a book in our hands—the digital version is convenient at times, but for all sorts of reasons it is just lovely to see and hold a book.

Book lovers are also often book hoarders. It is very difficult to separate oneself from the books one has lived with, used, taught from and loved for many years. But the time has to come. Well, for some of us.

There is a common saying that ‘of the writing of books there is no ending’. It actually comes from a Bible passage in the book of Ecclesiastes, where the tired and somewhat resigned author warns his hearer, addressed as ‘my son’: Of making many books there is no end, and much study is a weariness of the flesh. (Ecclesiastes 12. 12)

Perhaps: but who would live without them?!

Recently I read about an Oxford scholar of the first half of the last century, who was renowned for his extraordinary collection of books. His house was simply full of books, so much so that even to enter one had to navigate a passageway between piles of books.

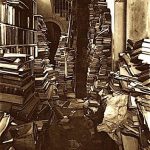

His name was Claude Jenkins (1877 – 1959), Regius Professor of Ecclesiastical History and Canon of Christ Church. An Anglican clergyman and theologian, Jenkins was the official Lambeth Librarian from 1910 until 1952 and was indeed notorious for his collection of books. A photograph survives of the hallway of his house in 1934. It was estimated that he had some 30,000 books in his home.

I learned about him because he was the supervisor for the research degree undertaken by Mervyn Himbury at Oxford. I am researching a biography of Himbury, who was Principal of Whitley College when I was a student there.

Some time early in his career in Melbourne, Himbury offered the following reflection upon Claude Jenkins, in a short radio segment called Pause a Moment:

I had a remarkable old tutor when I was at the University. He was probably the best read man I have ever known. Every week, like so many other students, I used to go to see Canon Claude Jenkins in his rooms at Christ-church.

Once the door was opened one was confronted by an amazing sight.

Everywhere there were books with a narrow passageway between them

leading to his study. By his chair was a little table. He would sit there while I sat on the other side, getting up now and again to peer over the pile of books on that table which grew to a remarkable height as the term went on.

He read widely and voraciously on every subject you could imagine. Yet I always remember his last words to me as I was about to come down from the University.

“Master Mervyn,” he said, with his usual quaint old world expression, “You will find great joy in your books but always remember that if there is ever a choice between reading a book and speaking to a person who may need your help, put the book away.”

Help us, 0 Lord, always to remember the importance of other people.

Jenkins, and Himbury, knew the value of books, but they knew too that people were so much more important: and as we learn the value of each we come to realise that each of us is in a sense writing a book, a story perhaps, with many chapters and lessons, twists and turns, not to be piled up but to be opened, offered and read, and (yes) eventually put away as new ones come along. But meanwhile, our books and lives are treasured and loved.

The entrance hall to Jenkins’ home: