At the weekend we went to see the marvellous exhibition titled The Body Beautiful in Ancient Greece at Bendigo Art Gallery.

It’s a superb collection of sculptures and pottery from Greek and Roman sources, from around 500 BCE to 200CE.

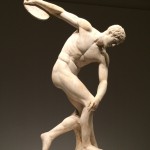

The centrepiece is the wonderful statue of a discus thrower, which we learned was actually found in the 19th century with his head off, and those who wished to restore it put the head on at a wrong angle.

There were so many other wonderful pieces: and with it all an interesting commentary on the place of the body in ancient Greek aesthetics, morality and culture.

Just a few observations. First, the most obvious feature of the entire exhibition is how male it is: almost all the figures are male, even though some were ‘feminised’, such as the sculpture of Aphrodite, below. Inherently, the philosophy and aesthetics saw the male body as superior, because it could be governed by reason while the female body was thought only to be governed by passions, emotions, and more broadly ‘hysteria’, which really just meant femininity. It was really a circular argument (of course, made by men, who were the only ones who did philosophy anyway. So no woman was there to critique this view of things.)

Yes, they are all male and on some of the pottery, at least, they are in erotic poses, with other males. In other instances, the erotic element or suggestion is heterosexual. However, to focus on the sexuality as such is to miss the major element in this aesthetic and the morality of the body in Greek culture.

It’s more than a little paradoxical, as the ultimate values of the culture reached towards the entirely disembodied ideals, or as Plato called them, ‘the forms’. The ultimate of reality, truth and goodness, in divinity or perfection, was by definition not bodily. Indeed it has no physical attributes, because these by nature are changing and that which is perfect cannot change: to do so would either mean it became less perfect or it was not perfect before it needed to change. Our bodies, on the other hand, constantly change, so they are not perfect in the way the gods, or at least the highest good, is perfect.

Still, the Greeks did envisage that gods (and the children of the gods) had bodies, and they sculpted their figures. Furthermore, they were able to use the term ‘divine’ to refer to the beautiful bodies of some young men. That brings us back to the ethic or morality of the body.

The Greeks believed in caring for and developing the body. That is why they developed athletics and the Olympic Games. At one very interesting point, Plato’s hero Socrates says to Epigenes, in Xenophon, “It is a disgrace to grow old through sheer carelessness before seeing what manner of man you may become by developing your bodily strength and beauty to their highest point.” Remember that as you are doing your laps or pounding the pavement!

Sport and recreation of many kinds were the means to an end: to develop the body and its beauty. The beauty and the achievement was the objective, and athletes were greatly admired.

One of the interesting things here is to consider the value placed on the body, albeit only in these artistic expressions male bodies. (There were many beautiful female figures too, as well as female gods, so it should not be thought that there was no appreciation of the female form. On the contrary.)

As I said before, there is something paradoxical in this appreciation of the young bodily form. First, it has all the hallmarks of Romanticism, as we later came to call it: there is the bitter-sweet appreciation of what is lovely, here and now, but with a strong and clear appreciation that this will soon pass. This body will grow old and perhaps fat or certainly less fit. This love will pass, the Romantics constantly said: we may love now, but not for long … Enjoy this beauty, here and now.

Then, too, it is fascinating to think of this as the background to so much of our New Testament thinking about human life, bodies, and the idea of a collective ‘body’, as Paul coined this idea, the body of Christ.

Despite a common misunderstanding, Paul did not disparage the human body or ‘flesh’. He placed such a high value on bodily life that he referred to our embodied life together as the place where God dwells, the temple of the Spirit. And for Paul, it is not in some inner, disembodied ‘soul’ that we are to love and serve God, but in our mortal bodies. (Paul’s letters to the Corinthians are full of this theme.)

John’s theology takes it even further, insisting that the very being of God, the only God, creator and lord of all, has become a human and dwelt among us in bodily form. Here John takes the Greek ideals head-on. This God is not a demi-god, or a lesser being, but is the very being of God and yet takes physical flesh, is thirsty, hungry, grieves, and suffers death. It is fascinating that this theology emerged during the same centuries as the Greek ideals of the body beautiful. In contrast to the Jewish insistence that God has no such form, that it is impossible to see or image God, both the Greeks and the Christians envisage divinity embodied, though to radically different effect.

There is so much to delight in, in these expressions of the life God has created: human life and beauty. It is tragic that in so many ways Christianity de-valued the body and disavowed beauty in many of its forms. Somehow or other the men who controlled things were so frightened of their own sexuality they simply tried to pretend it wasn’t there. (What we now know is that that kind of attitude is precisely what produces many kinds of sexual perversion and exploitation.)

The body beautiful is an invitation to know something more of God’s creation, of our own history and life, individually and collectively, and something more of the world from which the New Testament emerged.