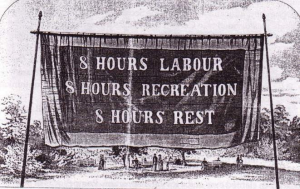

Yesterday in several Australian states it was a public holiday. In Victoria it is called ‘Labour Day’. It commemorates the foundations of the Labour movement here, where workers on the new buildings for the University of Melbourne went on strike, in April 1856, in support of the Eight Hours Movement.

It’s intriguing in a way that it is called ‘Labour Day’. In Tasmania, the public holiday held on the same day is called Eight Hours Day. I say ‘intriguing’ because in its most basic purpose the movement was not primarily about work, but about a limitation on how many hours people should be required to work. In essence, the movement was about the other 16 hours: recreation and rest.

The Labour Movement gave rise to the Trade Unions and in due course the Labor Party. But what is important here, I think, is the fundamental community movement behind this vision for rest and recreation. It had its origins in the industrial north of England and was very strongly associated with, though not ‘officially, the Methodist churches. Welsh and Irish influences were also part of it. These community movements expressed themselves in strong ‘co-operatives’, which provided support for what are today called ‘working families’, especially in times of hardship and need, but more generally as well.

So if work is limited to eight hours a day, what of the other 16 hours? Eight hours rest was self-explanatory. But a significant question in this movement was precisely what would people do with eight hours of recreation. Some of it, of course, was spent going to and from work, getting clean, and the fundamentals of home life: care for children, eating and enjoying the company of one’s partner and friends.

But it was in these hours that the movement contributed much more than limiting working hours and improving working conditions. Along with those vital elements, there were such things as the ‘Mechanics Institutes’, which were essentially adult education centres, many of them associated with lending libraries. (One such institute was formed in Scotland as early as 1796.) People read newspapers and books, avidly. And many enjoyed drama and poetry, far more so than today.

I have seen the transcripts of lectures and addresses delivered in such places, in country towns around the state, on subject varying from the new critical approach to the Bible to the nature of healthy rest, as well as directly political subjects. The Mechanics Institute provided education to so many who had not had the opportunity to go to school beyond the primary years. This was another form of the co-operative movement, which lasted well into the twentieth century in many places. It went hand in hand with the movement for democratic government, initially for working men who did not own land to be allowed to vote and as the century was closing women also to vote—first in South Australia in 1894. Already, the introduction of ‘free, compulsory and secular’ schooling, for all children, throughout all the states of Australia (actually ‘colonies’ still) was a massive expression of the same progressive movement.

As we have enjoyed this holiday in commemoration of the Eight Hours Movement, it is worth celebrating this wholesome vision of a balanced life. We say a lot about ‘work-life balance’ today, but it is rarely as positively asserted as this movement of our forebears. We have lost something of the importance of all the elements: the boundaries between work and recreation are less clear, as our devices go with us everywhere, and we are so much more ‘available’.

I rather suspect that the central wisdom here lies in the idea of eight hours recreation. It’s an interesting word: re-creation. Receiving life again. Becoming ourselves again. That may reflect something of Marx’s assertion that for most people work is a kind of alienation: we are not our own, we are not able to be ourselves when we are at work, under orders. That’s not true of everyone, but there is an element of truth in it.

Recreation is a time to take stock of ourselves, to own our life situation, affirm what we truly value, and enjoy it. And this is not once a week, at the footy match, or whatever: this is for every day!

How much better our life, and for that matter our sense of worship, would be if this was indeed our every day, and with it the weekends!

Here there is something life-giving, which surely lies at the heart of our creation as human beings, made in the image of God, capable of work and rest, and recreation.